Shot Out of a Volcano at Last!

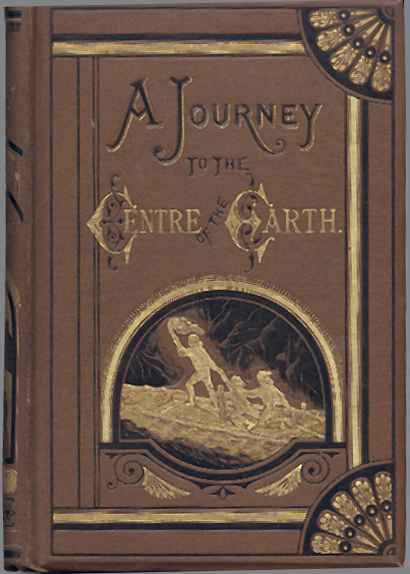

Jules Verne (1828–1905) was a French author, who along with H. G. Wells, is often referred to as the "father of science fiction." He was the author of numerous works that remain popular to this day, including Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870) and Around the World in Eighty Days (1873). One of his earliest successes was A Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864). The novel concerns the subterranean adventures of a party of explorers who enter the Earth through the volcanic crater Snaefellsjokull in Iceland (see location to the right). The excerpt below describes how the party exits from the depths of the Earth:

... "My uncle," I cried, "we are lost now, utterly lost!"

"What are you in a fright about now?" was the calm rejoinder. "What is the matter with you?"

"The matter? Look at those quaking walls! Look at those shivering rocks. Don't you feel the burning heat? Don't you see how the water boils and bubbles? Are you blind to the dense vapors and steam growing thicker and denser every minute? See this agitated compass needle. It is an earthquake that is threatening us."

My undaunted uncle calmly shook his head.

"Do you think," said he, "an earthquake is coming?"

"I do."

"Well, I think you are mistaken."

"What! don't you recognize the symptoms?"

"Of an earthquake? No! I am looking out for something better."

"What can you mean? Explain?"

"It is an eruption, Axel."

"An eruption! Do you mean to affirm that we are running up the shaft of a volcano?"

"I believe we are," said the indomitable Professor with an air of perfect self-possession; "and it is the best thing that could possibly happen to us under our circumstances."

The best thing! Was my uncle stark mad? What did the man mean and what was the use of saying facetious things at a time like this?

"What!" I shouted. "Are we being taken up in an eruption? Our fate has flung us here among burning lavas, molten rocks, boiling waters, and all kinds of volcanic matter; we are going to be pitched out, expelled, tossed up, vomited, spit out high into the air, along with fragments of rock, showers of ashes and scoria, in the midst of a towering rush of smoke and flames; and it is the best thing that could happen to us!"

"Yes," replied the Professor, eyeing me over his spectacles, "I don't see any other way of reaching the surface of the Earth."

... It was very evident that we were being hurried upward upon the crest of a wave of eruption; beneath our raft were boiling waters, and under these the more sluggish lava was working its way up in a heated mass, together with shoals of fragments of rock which, when they arrived at the crater, would be dispersed in all directions high and low. We were imprisoned in the shaft or chimney of some volcano. There was no room to doubt of that.

... I have therefore no exact recollection of what took place during the following hours. I have a confused impression left of continuous explosions, loud detonations, a general shaking of the rocks all around us, and of a spinning movement with which our raft was once whirled helplessly round. It rocked upon the lava torrent, amidst a dense fall of ashes. Snorting flames darted their fiery tongues at us.

... When I opened my eyes again I felt myself grasped by the belt with the strong hand of our guide. With the other arm he supported my uncle. I was not seriously hurt, but I was shaken and bruised and battered all over. I found myself lying on the sloping side of a mountain only two yards from a gaping gulf, which would have swallowed me up had I leaned at all that way. Hans had saved me from death whilst I lay rolling on the edge of the crater.

... Above our heads, at a height of five hundred feet or more, we saw the crater of a volcano, through which, at intervals of fifteen minutes or so, there issued with loud explosions lofty columns of fire, mingled with pumice stones, ashes, and flowing lava. I could feel the heaving of the mountain, which seemed to breathe like a huge whale, and puff out fire and wind from its vast blowholes. Beneath, down a pretty steep declivity, ran streams of lava for eight or nine hundred feet, giving the mountain a height of about 1,300 or 1,400 feet. But the base of the mountain was hidden in a perfect bower of rich verdure, amongst which I was able to distinguish the olive, the fig, and vines, covered with their luscious purple bunches.

... "Where are we? Where are we?" I asked faintly.

... "STROMBOLI," replied the little herdboy, slipping out of Hans' hands, and scudding into the plain across the olive trees.

We were hardly thinking of that. Stromboli! What an effect this unexpected name produced upon my mind! We were in the midst of the Mediterranean Sea, on an island of the Aeolian archipelago, in the ancient Strongyle, where Aeolus kept the winds and the storms chained up, to be let loose at his will. And those distant blue mountains in the east were the mountains of Calabria. And that threatening volcano far away in the south was the fierce Etna.

"Stromboli, Stromboli!" I repeated.

Click here to zoom in on the Stromboli Volcano in Italy.

Questions for Comprehension and Understanding:

- What does the central character initially think is causing the quaking motion at the beginning of the excerpt?

The central character initially thinks that an earthquake is causing the quaking motion. - According to the Professor, what is the actual cause of the quaking motion?

The Professor states that the quaking motion is actually being caused by a volcanic eruption. - How does the party of adventurers escape from the volcano?

The party escapes by riding on a raft that is carried up the shaft of a volcano by a volcanic eruption. - Where does the party eventually emerge after being expelled by the volcano?

The volcano deposits them on the side of Stromboli, a volcano on an island in the Mediterranean (off the coast of Italy). -

- The party starts their trip at Snaefellsjškull, Iceland and ends it at Stromboli, Italy. Click here and then use the measuring tool to determine the distance from Snaefellsjškull, Iceland to Stromboli, Italy.

The distance is approximately 3,900 km (2,423 miles). - The explorers are underground for approximately 98 days. Calculate the average distance (in km, accurate to two significant digits) they would have had to travel each day in order to complete their journey.

They covered 3,900 km in 98 days or an average of approximately 40 km (25 miles) per day (accurate to two significant digits).

- The party starts their trip at Snaefellsjškull, Iceland and ends it at Stromboli, Italy. Click here and then use the measuring tool to determine the distance from Snaefellsjškull, Iceland to Stromboli, Italy.