There are two primary methods to determine the strength of an earthquake. The first is based on the intensity of the earthquake. Intensity is measured by how much damage an earthquake has done. A person’s subjective impressions are used for very weak earthquakes that do not cause any physical damage.

The Mercalli Scale

The Mercalli Scale, a scale based on intensity, was developed in 1902 by Guiseppe Mercalli. Mercalli’s original ten level scale has since been modified to a 12 level scale, and is now known as the Modified Mercalli Scale. Level V on this scale describes an earthquake in which the earthquake is “Felt by nearly everyone; many awakened … Some dishes, windows broken.” A level X earthquake results in “most masonry and frame structures destroyed with foundations. Rails bent.”

There are a number of problems associated with using intensity as a measure of the strength of an earthquake. Factors such as building design, population density, and the nature of surface materials can have a great affect on the damage caused by an earthquake. In addition, the Mercalli Scale cannot be used on earthquakes that occur under oceans, or in uninhabited areas.

The Mercalli Scale is a qualitative scale; it depends solely on a person’s perceptions, or on a visual description of the effect of an earthquake.

The Richter Scale

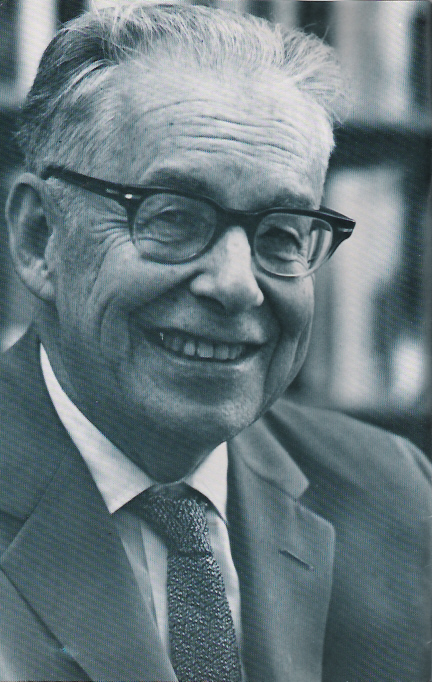

The second and more widely used method to determine the strength of an earthquake is based on the magnitude, or size of the seismic waves. Magnitude is determined by measuring the amplitude or height of the largest seismic wave that an earthquake generates. This kind of scale is a quantitative scale since it is based on actual measurement of a certain quantity, in this case, the wave’s amplitude. Such a scale was generated by the American physicist, Charles F. Richter in 1935.

The Richter scale is a logarithmic scale. This means that for every number that you go up in the scale, the actual amplitude of the seismic wave has increased by 10. This means that a magnitude 5 earthquake has 10 times the amplitude (or ground shaking) of a magnitude 4 quake, but 100 times the amplitude of a magnitude 3 quake (i.e. 10 x 10). Earthquakes of less than 2 on the Richter scale are generally not perceptible, while the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906 registered 7.8 on the Richter scale. An earthquake of magnitude 5.3 would be considered a moderate earthquake, while an earthquake of magnitude 6.3 would be considered to be a strong earthquake (with 10 times the amplitude of the 5.3 earth quake).

When he introduced his scale, Richter realized that he needed to standardize it so that it would be universally applicable. He did this by assigning a magnitude of 3 to an earthquake that occurred 100 km away with an amplitude of 1 mm. Thus, an earthquake that occurred 100 km away with an amplitude of 10 mm (i.e., 10 x 1) would have a magnitude of 4, while a magnitude 5 earthquake at a distance of 100 km would have an amplitude of 100 mm (i.e., 10 x 10). The modern magnitude scale has been modified and extended since Richter’s original 1935 scale, but it is still based on similar concepts.